Tuesday☕️

Trending:

- On January 26, 2026, Sergeant First Class (SFC) Ran Gvili was returned to Israel after 843 days in captivity in Gaza, marking the final release of all remaining Israeli hostages held by Hamas and other groups. Israeli officials confirmed his safe arrival home, ending a prolonged hostage crisis that began with the October 7, 2023 attacks.

- With Gvili’s return, there are now officially no more Israeli hostages in Gaza. The release followed negotiations involving mediators (including Qatar, Egypt, and the United States) and came amid ongoing ceasefire implementation efforts. No specific details on the circumstances of his handover or immediate condition were released in initial statements, but celebrations were reported in Israel upon confirmation of his return.

Economics & Markets:

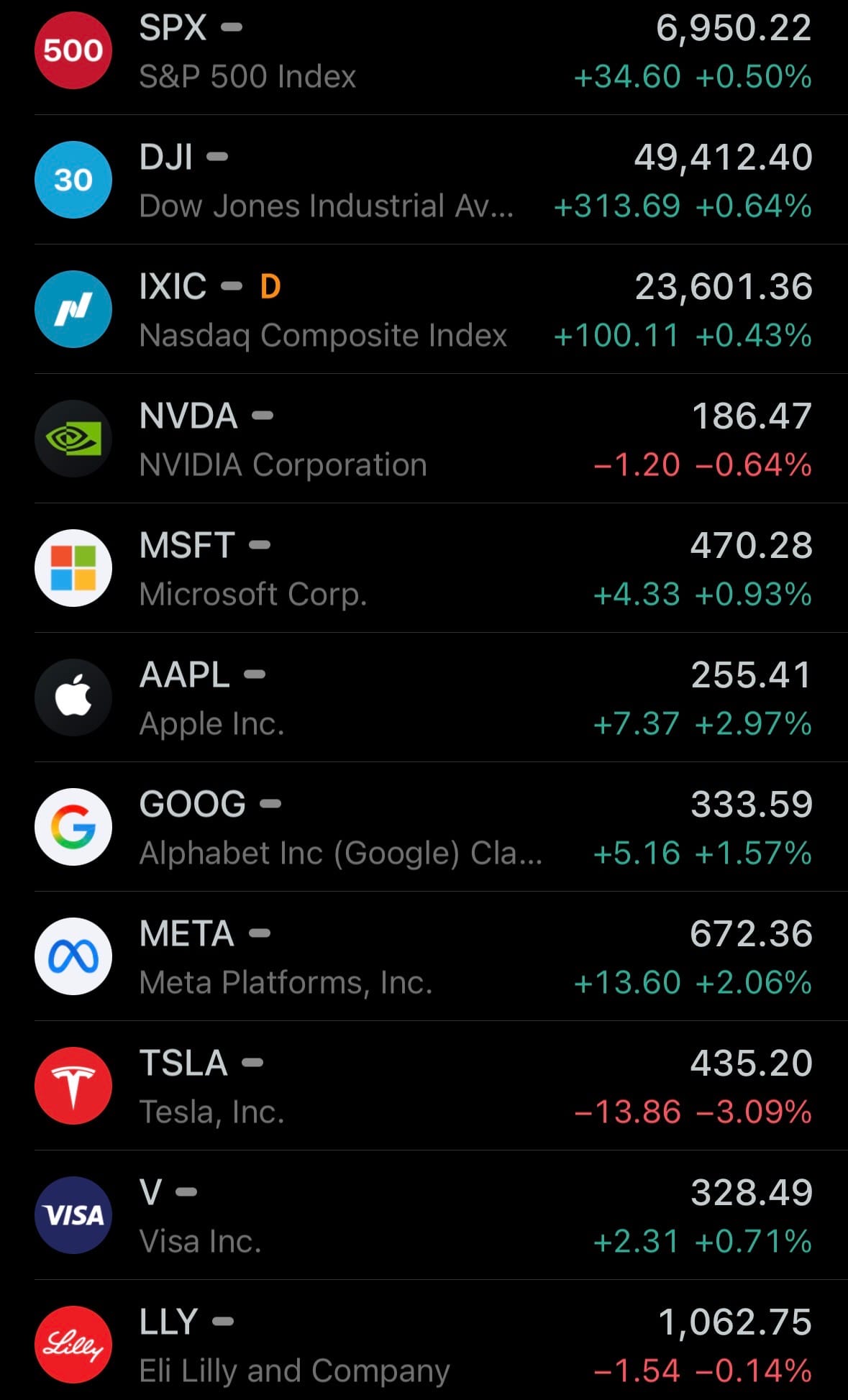

- Yesterday’s U.S. stock market:

- Yesterday’s commodity market:

- Yesterday’s crypt market:

Geopolitics & Military Activity:

- On January 26, 2026, Russian forces began withdrawing from Qamishli International Airport in northeastern Syria, one of their last major outposts in the north. Fighter jets, helicopters, and other equipment are being loaded onto Il-76 transport planes and moved mainly to Russia’s primary base at Hmeimim on the Syrian coast. The pullout follows reports that Syria’s post-Assad transitional government has prepared a formal request for Russia to vacate the airport, which Moscow has used since 2019 under an agreement with the former Assad regime.

- For Russia, losing Qamishli is a significant setback. It eliminates a key forward base in the north used for reconnaissance, logistics, and limited operations, confining their military presence entirely to the coastal stronghold of Hmeimim air base. This greatly reduces Moscow’s ability to project power, monitor events, or respond quickly in northeastern Syria, where the SDF and Kurdish-led groups dominate. The withdrawal highlights Russia’s weakened position after Assad’s collapse: fewer operating locations, less influence over northern developments, and diminished leverage in talks with the transitional government and other actors.

Environment & Weather:

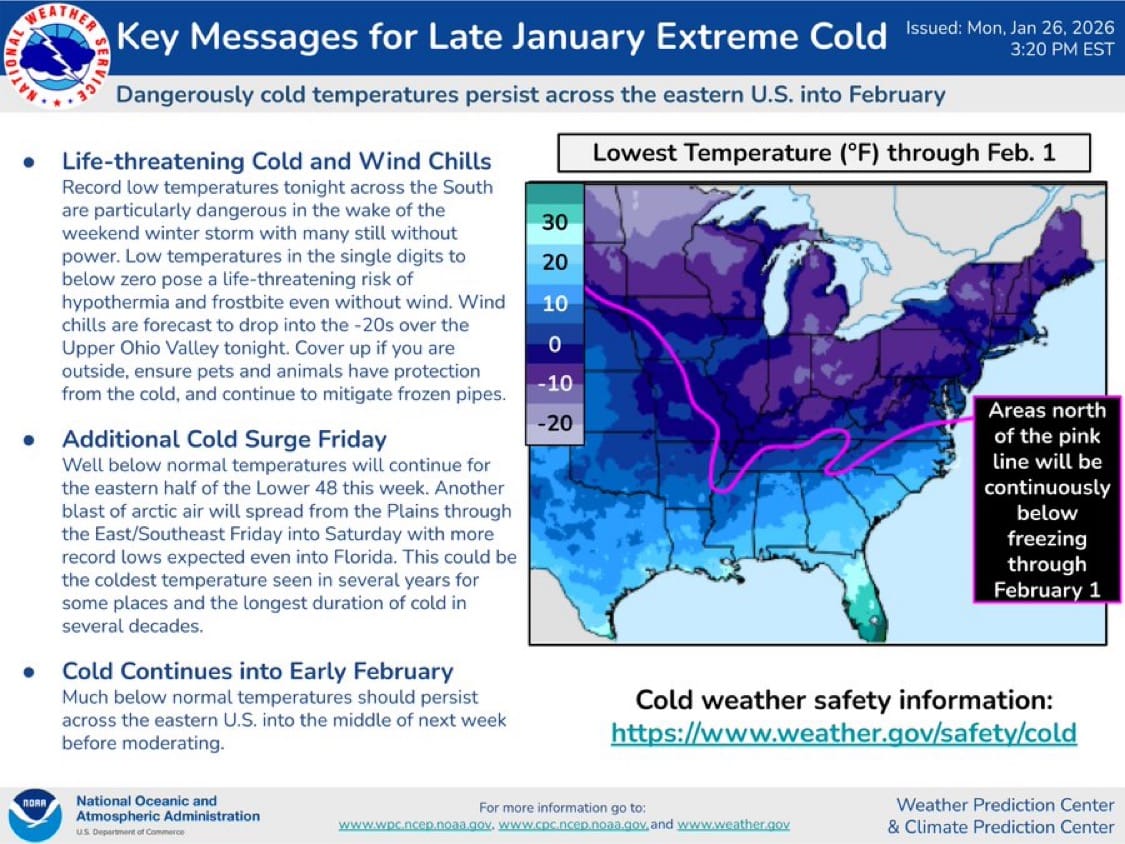

- On January 26, 2026, the National Weather Service warned of life-threatening extreme cold continuing across much of the eastern U.S. into early February. Record lows are expected in the South (single digits to sub-zero), worsened by the recent storm that left many without power. Wind chills will reach -20°F or lower in the Upper Ohio Valley, raising serious risks of hypothermia and frostbite with even brief outdoor exposure.

- The cold will persist through the week across the eastern half of the Lower 48 (Great Lakes, Upper Midwest, Ohio Valley, Appalachians, Mid-Atlantic, and South). Areas north of the pink line on NWS maps (roughly northern Plains to Northeast) will stay below freezing through at least February 1, keeping frozen pipes, power outages, and travel hazards in place. A new arctic blast hits Friday into Saturday, pushing record lows into Florida and the Southeast—potentially the coldest in years and the longest cold spell in decades for some spots.

Science & Technology:

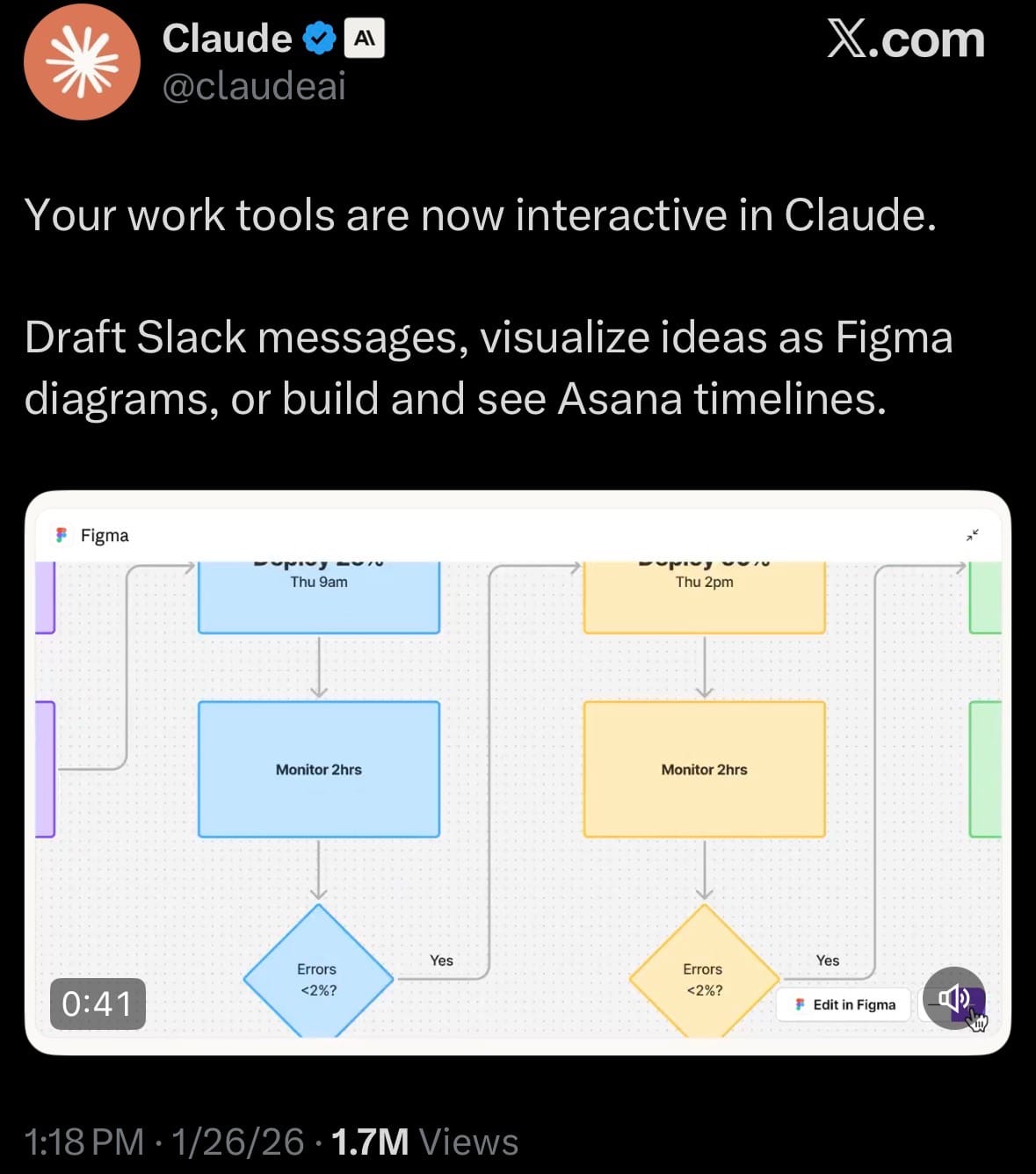

- On January 26, 2026, Anthropic announced that Claude now supports interactive work tools directly in its interface. Users can draft Slack messages, create and edit Figma diagrams to visualize ideas, or build and view Asana timelines—all within Claude conversations.

- These features are currently rolling out to Claude Pro and Max subscribers in the US, with opt-in access via the Claude desktop/web app. The tools integrate Claude's reasoning to generate content (e.g., writing professional Slack drafts, suggesting Figma layouts from descriptions, or auto-populating Asana project timelines based on goals and deadlines). Early access shows improved productivity for collaborative work, with privacy controls ensuring data stays within the user's workspace integrations.

Statistic:

- Largest public automakers by market capitalization:

- 🇺🇸 Tesla – $1.447T

- 🇯🇵 Toyota – $295.44B

- 🇨🇳 BYD – $124.04B

- 🇨🇳 Xiaomi – $117.73B

- 🇰🇷 Hyundai – $88.84B

- 🇺🇸 General Motors (GM) – $75.62B

- 🇩🇪 BMW – $63.34B

- 🇩🇪 Volkswagen – $62.99B

- 🇮🇹 Ferrari – $60.88B

- 🇩🇪 Mercedes-Benz – $60.88B

- 🇺🇸 Ford – $53.55B

- 🇮🇳 Maruti Suzuki India – $53.22B

- 🇮🇳 Mahindra & Mahindra – $46.55B

- 🇩🇪 Porsche – $45.71B

- 🇰🇷 Kia – $41.58B

- 🇯🇵 Honda – $38.99B

- 🇨🇳 Seres Group – $28.70B

- 🇳🇱 Stellantis – $27.96B

- 🇯🇵 Suzuki Motor – $27.29B

- 🇨🇳 Great Wall Motors – $26.16B

- 🇨🇳 SAIC Motor – $24.15B

- 🇨🇳 Geely – $23.12B

- 🇨🇳 Chery Automobile – $22.00B

- 🇮🇳 Hyundai Motor India – $20.06B

- 🇺🇸 Rivian – $19.30B

History:

- Air traffic control begins as a human problem long before it becomes a technical one: once aircraft exist in numbers, someone has to decide who flies where, when, and at what altitude so they don’t collide. In the earliest days of flight in the 1900s–1920s, there was no real control system—pilots flew visually, avoided each other by sight, and landed when runways were clear. As commercial aviation expanded in the 1920s and 1930s, basic coordination emerged: ground personnel used flags, lights, clocks, and radio calls to sequence takeoffs and landings. The first true air traffic control towers appeared in the 1930s, relying entirely on visual observation and radio communication. Everything changed with radar, developed rapidly during World War II. Radar made it possible to “see” aircraft beyond visual range and in bad weather, transforming airspace from a shared visual environment into a monitored volume. After the war, civil aviation adopted military radar technology, and by the 1950s, countries began building national air traffic control systems to handle rapidly growing jet traffic. Tragic midair collisions in the 1950s—most notably over the United States—forced governments to centralize control, standardize procedures, and separate aircraft vertically and horizontally. This era established the core ATC logic that still exists today: structured airways, altitude separation, controlled airspace, and continuous communication between pilots and controllers.

- From the 1960s through the 1990s, air traffic control became a large-scale, radar-driven command-and-control system. Ground-based primary radar tracked aircraft positions, while secondary surveillance radar added transponders that allowed controllers to identify aircraft and see altitude information. Standard transponder modes emerged, allowing aircraft to broadcast identity and altitude electronically, reducing ambiguity and controller workload. Airspace was divided into sectors staffed by trained controllers who managed traffic flow much like air traffic managers on a highway system—but in three dimensions and at high speed. As traffic density exploded, automation began creeping in: computer-assisted tracking, conflict alerts, and digital flight plans replaced manual plotting. International coordination became essential as aviation globalized, leading to harmonized rules, procedures, and phraseology so aircraft could cross borders seamlessly. By the end of the 20th century, ATC had become one of the most safety-critical systems on Earth—quietly coordinating tens of thousands of flights per day with extremely low error tolerance—yet it was still fundamentally radar-centric, ground-heavy, and constrained by infrastructure built decades earlier.

- Modern air traffic control is undergoing its most significant transformation since radar, shifting from ground-based observation to satellite-driven surveillance and data-centric management. The key change is automatic position broadcasting: aircraft now use satellite navigation to determine their own position and continuously transmit it via modern transponder systems, allowing far more precise tracking than radar alone. This enables tighter spacing, more flexible routing, and better fuel efficiency. Next-generation systems integrate satellite-based navigation, digital communications, real-time weather, and predictive flow management into a single network that manages airspace proactively rather than reactively. Controllers increasingly act as system managers rather than manual traffic directors, overseeing automated conflict detection and resolution tools. Major players include national aviation authorities that manage civil airspace, international coordination bodies that standardize procedures, aircraft manufacturers embedding advanced avionics, and airlines operating within tightly optimized global networks. Military and civil systems coexist but operate under different rules—military aircraft may limit or disable certain broadcasts during sensitive operations, while still being tracked through radar and defense networks. Today’s air traffic control is less about watching blips on a screen and more about orchestrating a global, continuously updating flow system—one that balances safety, efficiency, national security, and economic demand. It is an invisible infrastructure that makes modern aviation possible, turning crowded skies into one of the safest large-scale transportation systems humanity has ever built.

Image of the day:

Thanks for reading! Earth is complicated, we make it simple.

- Click below if you’d like to view our free EARTH WATCH globe:

- Download our mobile app:

Click below to view our previous newsletters:

Support/Suggestions Email:

earthintelligence@earthintel.news